FANTASTIC FEST 2024: "THE SEVERED SUN" (2024) Cast And Crew Discuss Their Brilliant and Beautiful Folk Horror Film (INTERVIEW)

As the sun shines down on the city of Austin, TX with it so do the lights of the Alamo Drafthouse in South Lamar for the 19th annual Fantastic Fest! For eight days, some of the best genre films worldwide will showcase the current and future talents in genre filmmaking while celebrating some classics in new, revitalized restorations. This year, Macabre Daily was fortunate enough to have some boots (well, one person) on the ground basking in the glory of all the genre has to offer. As part of our coverage, we will post reviews, interviews, and previews of upcoming films and games taking center stage here, including some exciting new horror games from the indie studios showcased in Fantastic Games presented by Day of the Devs! We are honored and privileged to be here, thank you to our partners at Fons PR, and now let’s get to the good stuff with an interview with Dean Puckett (Writer + Director), Ian Forbes (Cinematographer), Barney Harris (Actor), and Lewis Gribben (Actor) of “The Severed Sun” (read our review here) which Dark Sky Films have picked up for distribution!

*** This interview has been edited for length and clarity, please excuse grammatical errors***

Macabre Daily: Hello fiends, friends, and familiars this is Matt Orozco with Macabre Daily and I’m excited to be joined by some of the cast and crew of “The Severed Sun” which had its world premiere here at Fantastic Fest. Thank you so much, gentlemen, for the time. And I'll dive right into the questions, first for you, Dean, you know, congratulations on having this kind of world premiere and also getting the chance to share this with everybody. I did a little bit of looking into the background. You come from academia and also have done a lot of work in documentaries and short films. So with your first feature, what was the transition like for you?

Dean Puckett Well, the two things happened simultaneously, because obviously it took like, six years, seven years, to get the film made from the short, which is the kind of seed of this film, to the feature. I was actually working as a support worker for schizophrenics while I was writing the short and then I kind of fell into academia and started teaching while I was developing the feature film. So in all honesty, the two things kind of happened hand in hand. So I now work for the university in Cornwall. So, and I think, you know, one thing I'd say about teaching film is it's made me a better writer. Something about talking to young people, about trying to maybe explain to them, or help them get out of the way of themselves, or having to articulate maybe what's not right with their scripts, not right in inverted commas. Or, you know, kind of trying to maybe help them develop their screenplays, has made me a better writer, and then obviously, also a lot of students worked on this film. We shot this film on a very low budget in 12 days, and the only way we were able to do that is because we populated a lot of the crew with graduates, people who lacked experience, they more than made up for in energy. And yeah, so, actually, in the end, from the University where I work, became a partner in making the film.

MD: As someone who went through film school, knowing firsthand, that you don't always get a chance to work on something that actually gets seen by other people, right? A lot of times it's working in the hope that eventually someone will see something you do. So as far as your inspiration for the story? There's a very rich history of folk horror coming out of Europe, particularly in Western Europe. So what were the inspirations for the ideas that ended up in “The Severed Sun?”

DP: Well, obviously there’s the unholy trinity of “The Wicker Man”, “Blood on Satan’s Claw” and “The Witchfinder General”. But I would say beyond that, Michael Heinicke is a big inspiration for me. You know, there's that kind of community of people, and there's this underlying evil. And I think it was really about trying to bring take a make a folk horror in Britain and say something about where we are at as a country in some level, because all of those films, those famous old British folk horrors, are doing that, yeah, in one way or another. It's also interesting to say that, you know, when Matt Reeves made “The Witchfinder General”, he wasn't making a folk horror. He was making a Western. He was making his version of a Western in England. He only became known as a folk horror later down the line. It's a relatively new term, folk horror. None of those directors sat down and said, I'm gonna make a folk horror. Yeah, there was just a horror movie, right? There was just a horror movie or Western or whatever it was that they were trying to play with and so on that there's also some Western influence in in “The Severed Sun”, you know, like when you look at some of the frames and the compositions, it that that, that that is kind of inherent in the language of those folk horror things. So sometimes I think the genre definition can be tiny bit reductive, sure, but also it's helpful, and it's fun and it's nice, and I love those movies, and I love folk horror films, but I guess I'm sort of trying to take in all that influence and make something that brings something new to the table. And I do believe that we do that. I don't think there's anything that's quite like what we've made in the folk horror space. First of all, we've got a gnarly, weird, psychedelic creature. We've got proper gore in the movies, and there's a kind of macabre sense of humor, almost, which is influenced by Ken Russell, and “The Devils” is another film that I adore. I think it's about sort of taking in all those influences and trying to make something that says something about Britain metaphorically, but also tells a really good yarn and a good story.

MD: I mean, that's what we all kind of show up for, right? Is it just to see some people die in gloriously violent ways, but also, to have a good story while you're at it, right? Ian, as far as the visual language for the film, were there any kind of key inspirations you were looking at or trying to use that informed the way you wanted to shoot “The Severed Sun”?

Ian Forbes: Dean and I have ended up watching a lot of films together and talking about them. We've done that throughout the last six or seven years, and we've been working together so we don't like, necessarily break down the frame and analyze it like, you know, element by element. We kind of go off the feelings that we've had when we've seen the films, and then, you know. So I can tell when Dean's excited about something because we end up talking about it a lot. But really the actual kind of basis for the building of the language of this film and other projects that we worked on together, they start with, they start with storyboards. Dean draws them, and I get an idea of the size of the frame that he's thinking. They're drawn in a certain style. It's like a Dean-style drawing. And it makes me laugh because they are like, demonic!

DP: Good drawings, and demented.

IF: They crack me up because they give me a little answer into into his mind, and he effectively communicates the size of the frame that he's thinking, because he really sees the film in pictures. He also doesn't just see in pictures, because he'll be acting out when we get on the locations and we do the initial location scout. Or it might be just me and Dean, or it might be quite a lot of the crew there, other heads of department and Dean will be acting out for me. And then I can start to get a sense of how he sees the blocking. And then it's like with acting out his storyboards, all the films we watch together, the feelings, you know, the soundtracks, the places we've been together, you then I then go, all right, okay, yeah. And it's like, you know, I just don't know it feels right. We will change something based on our got really, it's like going off gut.

DP: But also we knew there was a certain slow burn pace to this film that we wanted it to have a kind of a slower rhythm that lends itself to, like, simple compositions, and it does. Like that scene where you're praying on that ledge. You know, you can shoot up and do two different angles. You put the hammer over the shoulder like it's just one wide from below, with the sun above your head. Just hold it. And I like stuff like that. I like it when a film feels very intentional. I think intentional is a good word that we would never want to shoot coverage, you know, like shot reverse, shot wide this and that every scene was like, Okay, we're gonna shoot this intentionally.

MD: It's very efficiently done. I think one of the challenges that ends up becoming a crutch, or not even a crutch, rather, a kind of a hindrance to a lot of horror films is that they do feel like filler sometimes. They're afraid to make a 70 or 80-minute film because that's what the story necessitates, rather than having to stretch something out for two hours. As far as the performances are concerned it seemed like you were always shooting on location So what kind of challenges, and also any interesting stories from the set were there for you Barney, and then Lewis?

Barney Harris: I think one of the great things about working with Dean was that he was sort of able to adjust to every actor's process individually. Some people are very easy to sort of go deep into the backstory and all of that, and others, you know, it was more, sort of a visceral approach. But yeah, with John, I think it was a case of sort of building up his journey into the community alongside Dean and how he placed himself, what he wanted from that situation, what he was scared of, and what he psychologically needed that wasn't being fulfilled, and why he was with the pastor…

DP: it was a difficult arc, actually, so it's quite hard to process because he plays, you know, trying to get into a character that is a believer that is losing their faith. That's complicated. It's complicated to orient yourself at that certain point, isn't it? It was a real constant conversation between us.

MD: Lewis, you kind of have a different approach, because your character goes a bit off of the deep end. Was it hard to get into that state of mind at some point, get a bit rabid?

Lewis Gribben: No. I mean, for me, like, I'm kind of what he was saying about visceral like, I'm the total opposite. If I talk about something too much, and if we go too much into backstory and everything it kind of kills my imagination. So Dean was very cool at letting m like me do my instinctual kind of feeling of what the scenes were and then guiding me slightly to if it was going too off-kilter. But for the most part, Dean let me do that. And I think with David being so disassociated with religion. You know, his dad being so abusive, the only good semblance of his life is not really his, which is his stepmom, slash, I guess, lover, and that's not even really his either. So it's sort of, he kind of has nothing. And it's sort of like he has nothing. He kind of has everything to gain, but, and that nothing to lose, kind of feeling so when he confronts John when John comes back, and I'll come back and he's just like he's heard it all before. He's so tired of, like, all this terrible stuff was happening to him, and the community didn't do anything. So I think playing something that was kind of an outsider, and I've played outsiders before, so it was kind of easy to tap into, and also, like you just that genuine thing of like if you'd be angry if you'd felt like abandoned in a way. So that's just a very human emotion that was not too hard to tap into.

BH: You could tell this story from the perspective of any of the characters, it's truly developed. To the extent that they all felt distinct from each other.

LG: They all worked together even though they were like in a different type of film, I don't think they would all fit. But I think in this kind of community where you have to be stuck in one place, you have the person that can love it, and, you know, like the pastor who feeds the grandiose and has all of it. And then you can have two people that feel so disassociated and want to have something completely different. And then you can have someone that's morally questioning his place as the new pastor, potentially, but doesn't want that kind of but it's forced into it because that's all he knows.

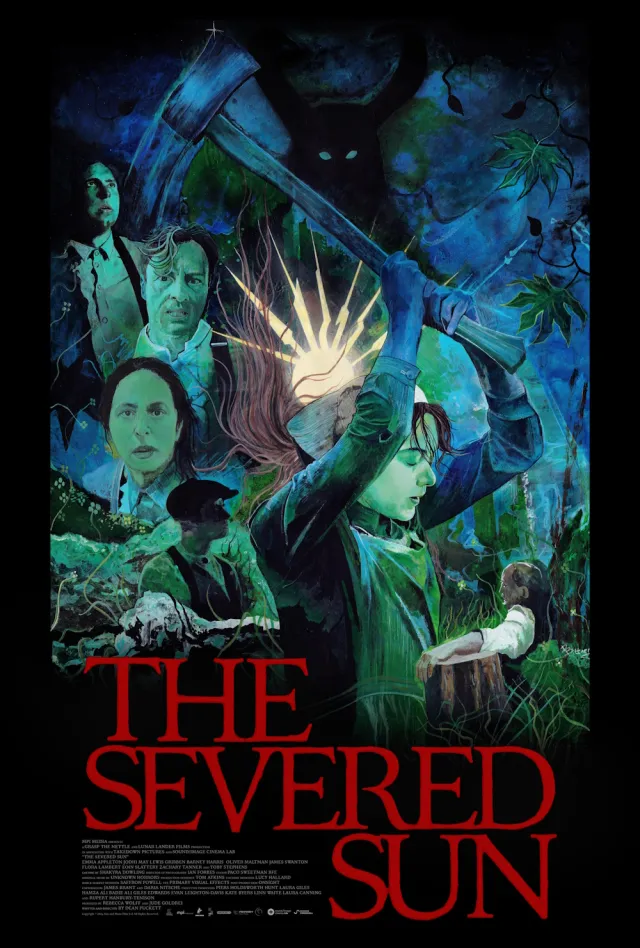

MD: It does feel like a very lived-in world, which I think is what first makes it so disorienting, is that you're trying to figure out, what is this place that I'm supposed to be I'm going to be here for the next 80 minutes. On a slightly adjacent note, I'm curious to know how you connected with Dom Bittner for the artwork because I have bought some of Dom's original art before.

DP: I follow a lot of alternative movie accounts on Instagram, and he painted a beautiful painting of “The Exorcist”, his own interpretation of “The Exorcist” poster. I just reached out and got in touch with him. It was a nice process, actually, similar to the way I work with the music guys. He said, “What do you want? Like, you know, what's the brief?” I said, “Look, you make all these beautiful posters for movies that you've watched from your imagination based on the film you've seen. So just watch the film and come up with some ideas for the poster.” You know, how does it inspire you? And he came up with three different black and white sketches, two of which have been made into posters, and I loved them. And that was lovely because no one else did. No one had even seen the film at this point, just him. And then he came back to me with these mad, amazing images. And I was like, Oh, that was actually a really exciting part of the process.

MD: His art style is very fitting to the kind of movie, exactly. So my last question for all of you, but if you were to be asked to program a double feature with “The Severed Sun", what is the other movie you program it with?

DP: I think I'd like to put it in with “The Devils” by Ken Russell. Yeah. Just the kind of the manic energy of that movie and how everyone's losing their minds. There's that kind of crossover between fantasy and reality. And to be, you know, like Andrea's journey in this movie, the woman that kickstarts the witch trial is very much inspired by Vanessa Redgrave in “The Devils” because she believes in that she's seeing things that she's not seeing. And there's a kind of erotic element to them as well and a repression. It's like they're exploding out of Vanessa Redgrave in “The Devils”, because she's repressing her true feelings, right? And although it's not the same as in “The Severed Sun”, is that Andrea's character doesn't want to look at what's going on in her own house, and so she's suppressing that feeling.

IF: I mean, I think Dean's answer is what I’d go with.

LG: Because it's also got that kind of weird cult vibe, and there's oddness in that I feel like It wouldn't be out of place if you put “Midsommar” next to this. Even though they're very different films, like they still have that weird kind of something that's not right. The shits getting weirder and weirder and weirder and weirder and yeah, I mean, I feel like if Dean had the money and budget, he could probably make something where a guy gets trapped as a giant teddy bear having that kind of mindset.

Stay up to date with “The Dark Side Of Pop Culture” by following Macabre Daily on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.